Questions remain about how the City will get there and how committed it is to overcoming obstacles.

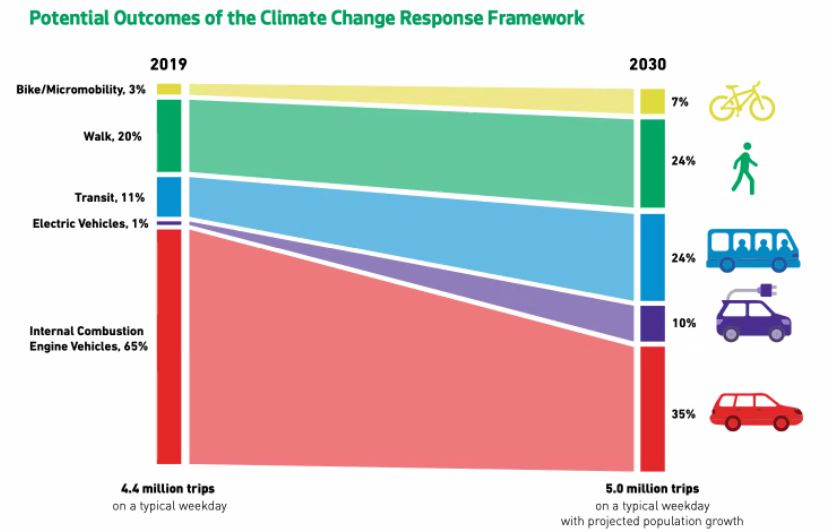

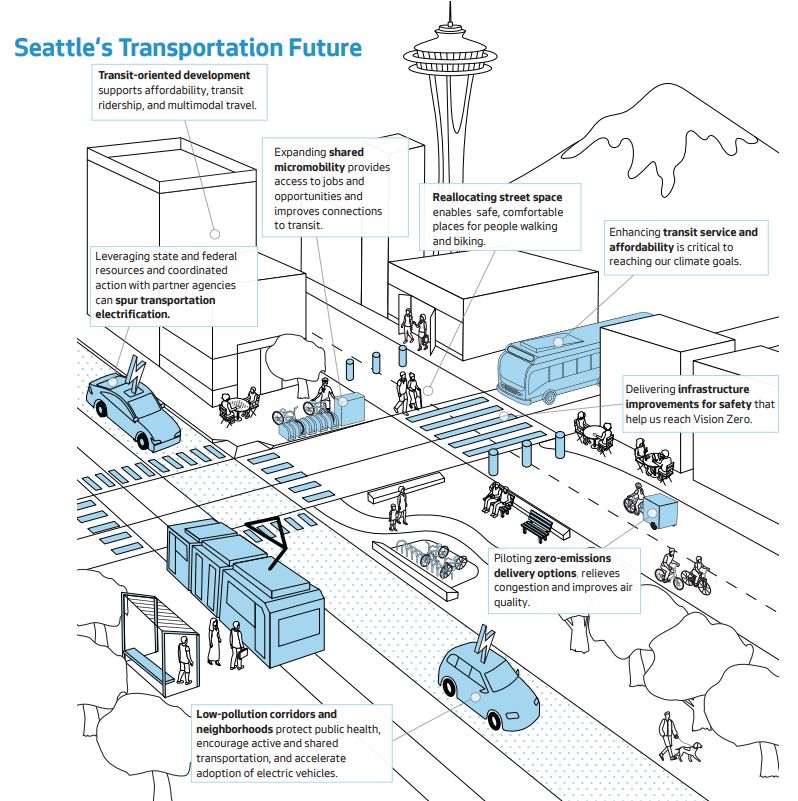

Transit would jump from 11% of trips to 24% of trips by 2030 if Seattle is able to meet the goal set in its recently released “Climate Change Response Framework.” Walking, rolling, and biking, meanwhile, would collectively jump from 23% to 31% if Seattle meets the 2030 goal. Internal combustion engine vehicles would shrink from 65% of trips to 35%.

As an addendum to the larger Seattle Transportation Plan, the framework clarifies goals and baselines that had been omitted in the previous document, but climate and multimodal advocates are pondering if those goals are in fact achievable if they are not integrated into the plan, and even more importantly, infused into Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) decision-making on a regular basis.

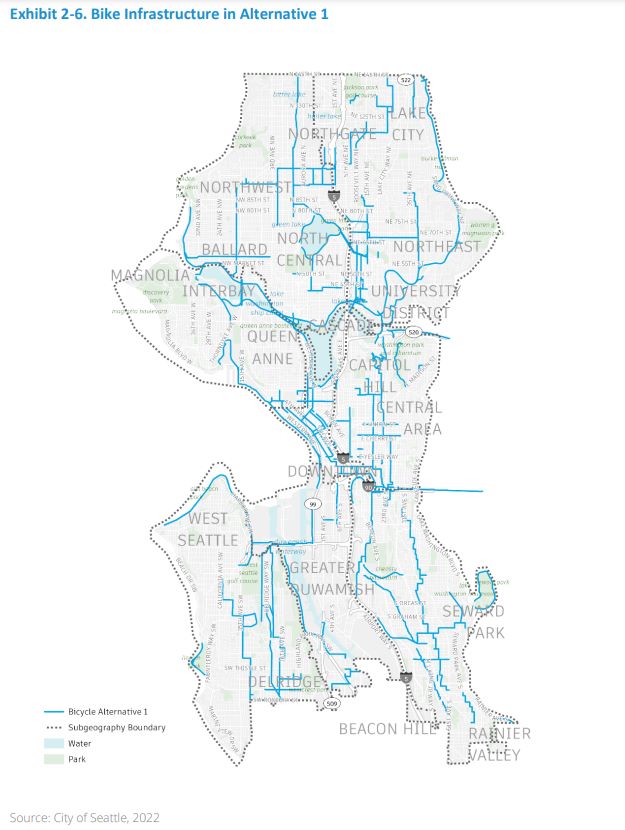

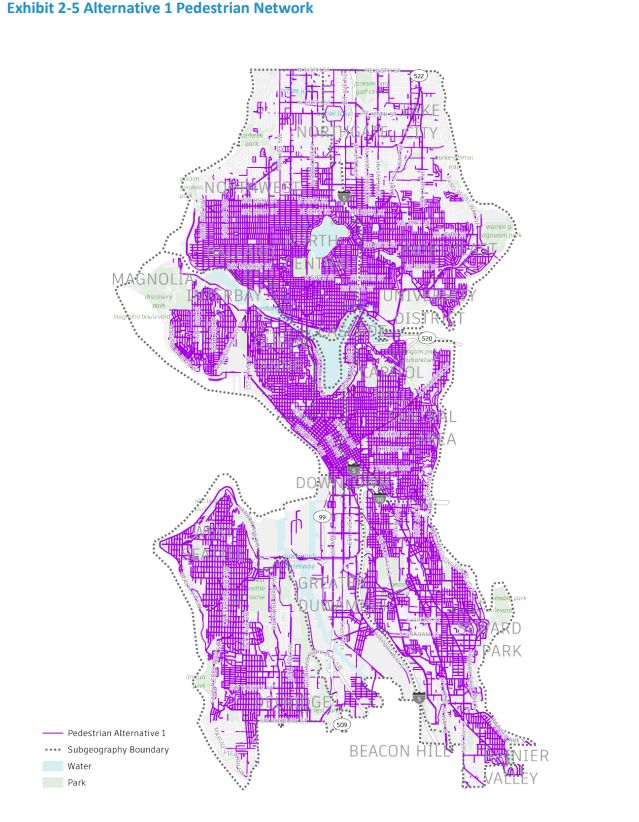

The Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the Seattle Transportation Plan does offer some clues as to how the city would hope to meet these goals even if momentum is fairly low right now, with transit service still not recovered to pre-pandemic levels and achingly slow progress on safety projects geared at enticing more walking, rolling, and biking, particularly compared to climate-leading cities like Paris. The way the City aims to turn the tide is by a rapid buildout of its sidewalk, bike, and dedicated transit networks — plus pedestrianization in some corridors via a bucket of funding the City is calling, People Streets and Public Space or PSPS, for short.

Essentially, this is the formula that cities like Paris have successfully used to curb emissions. Paris has added 600 miles of protected bike lanes, boosted transit networks, and expanded pedestrian zones, which led to a climate emissions drop to 20% even as the city population grew steadily. Locals reaped livability and health benefits from this change.

“Since 2011, Paris has reduced the amount of car traffic by about 45% and nitrogen oxide pollution — a common type of car pollution — by about 40%,” François Croquette, Paris’s director for climate and ecology told NPR.

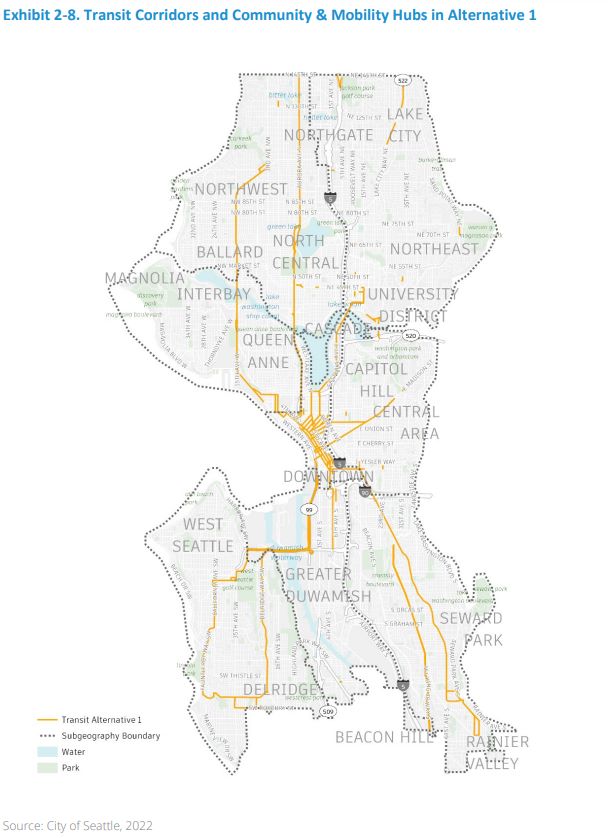

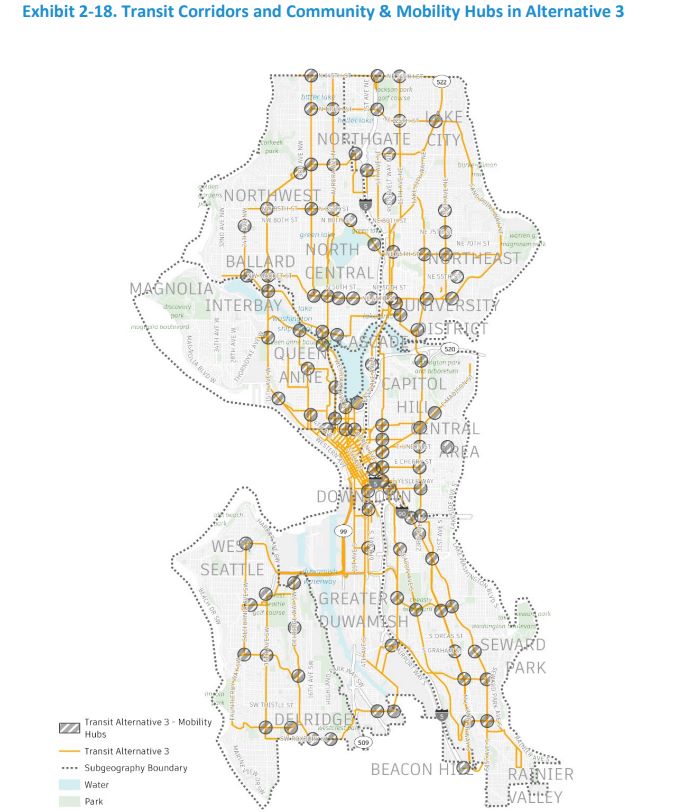

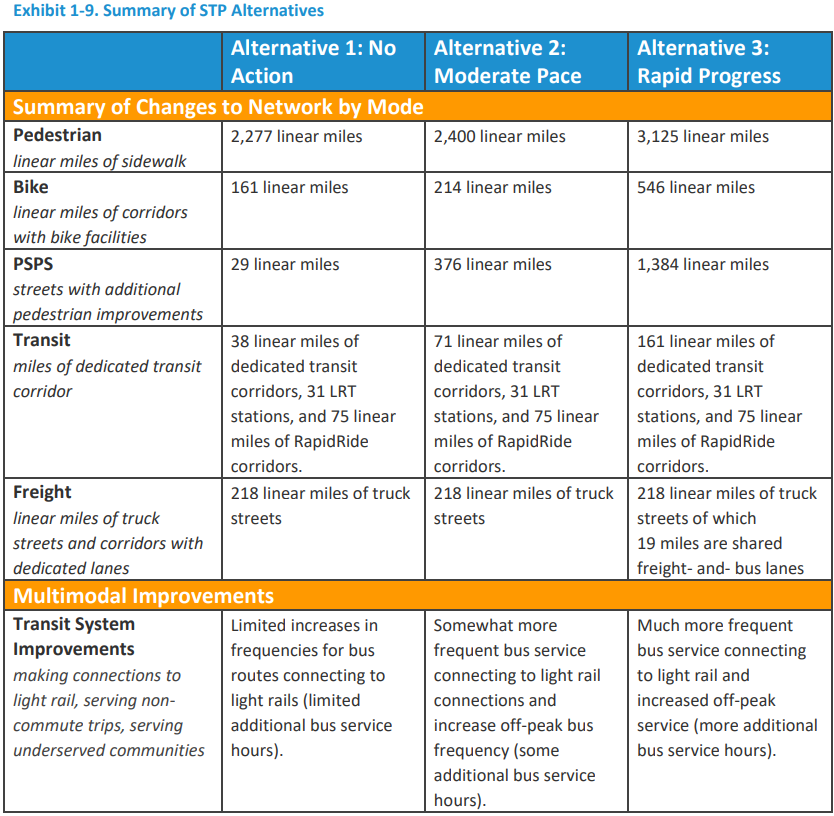

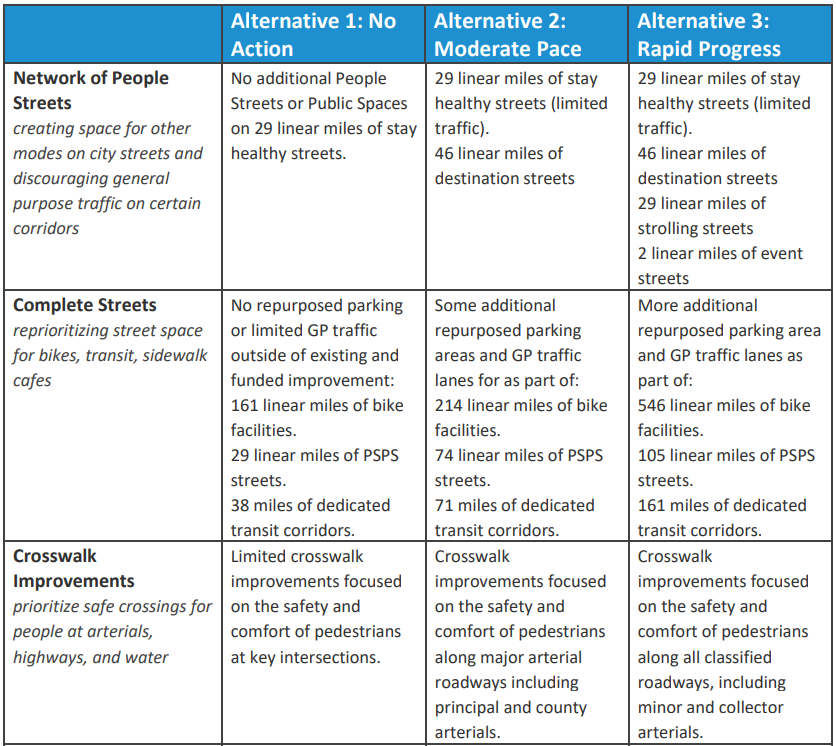

SDOT is studying three alternatives. Alternative 3 is dubbed, “Rapid Progress,” and delivers the fastest expansion of those emission-free transportation networks. The agency lays out the three alternatives as follows:

- Alternative 1 – No Action: Alternative 1 – “No Action is a SEPA-required alternative that would maintain existing transportation networks and approved funding commitments. Roadway operations are optimized at key intersections, limited spot safety improvements are made throughout the network, and very limited slow zones are implemented on key pedestrian spaces.”

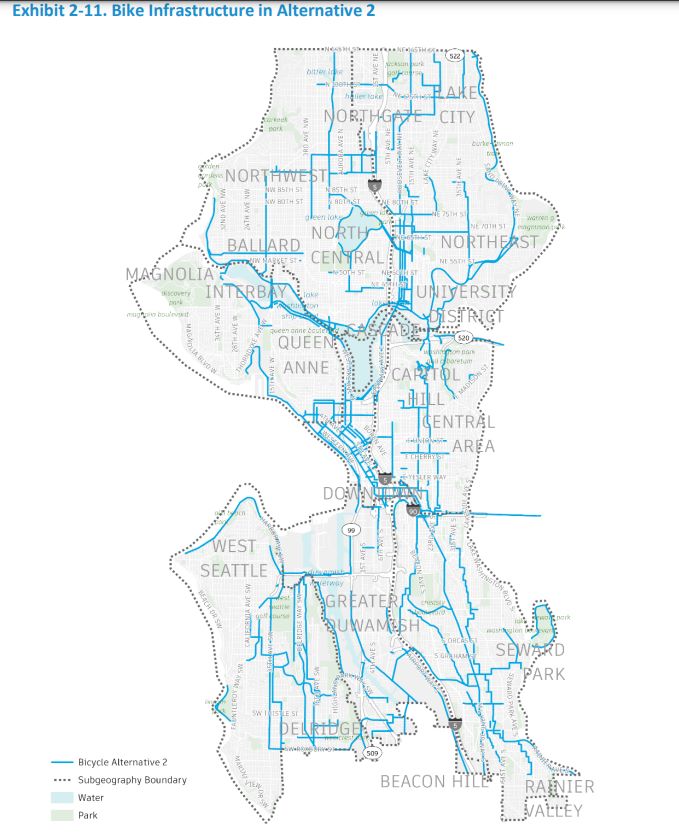

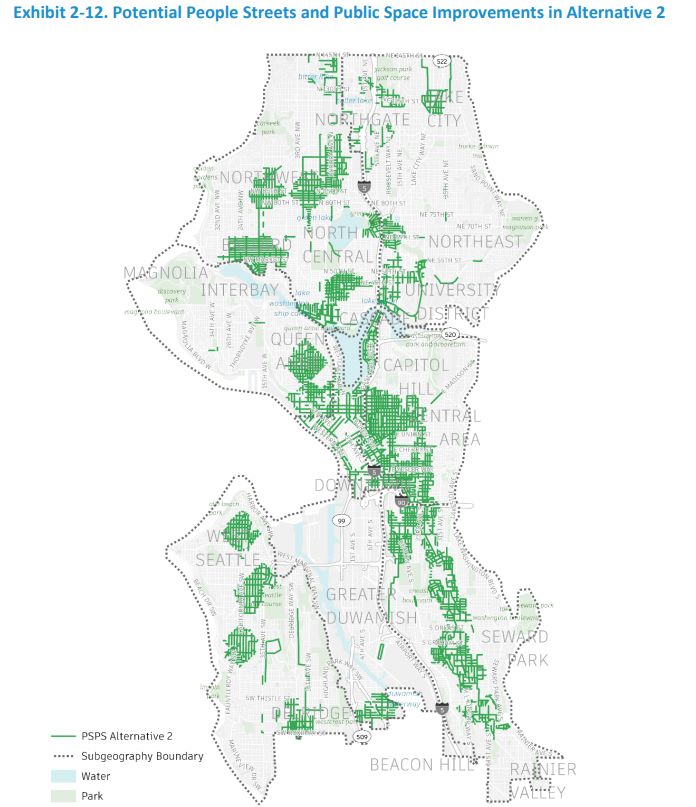

- Alternative 2 – Moderate Pace: “Alternative 2 allocates a moderate amount of new funding for multimodal infrastructure. The pedestrian network increases by 127 linear miles of sidewalks, the bicycle network adds 53 miles with facilities, an additional 45 miles of streets receive additional PSPS improvements, and 33 miles are dedicated as transit corridors. This plan includes some restricted areas for general purpose traffic, a network of People Streets, and a moderate number of community and mobility hubs. The existing freight network is unchanged.”

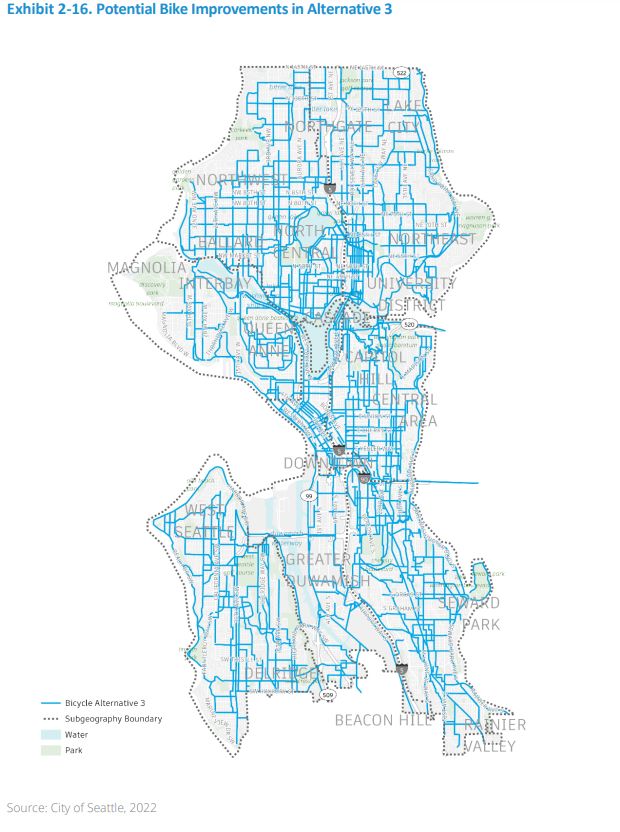

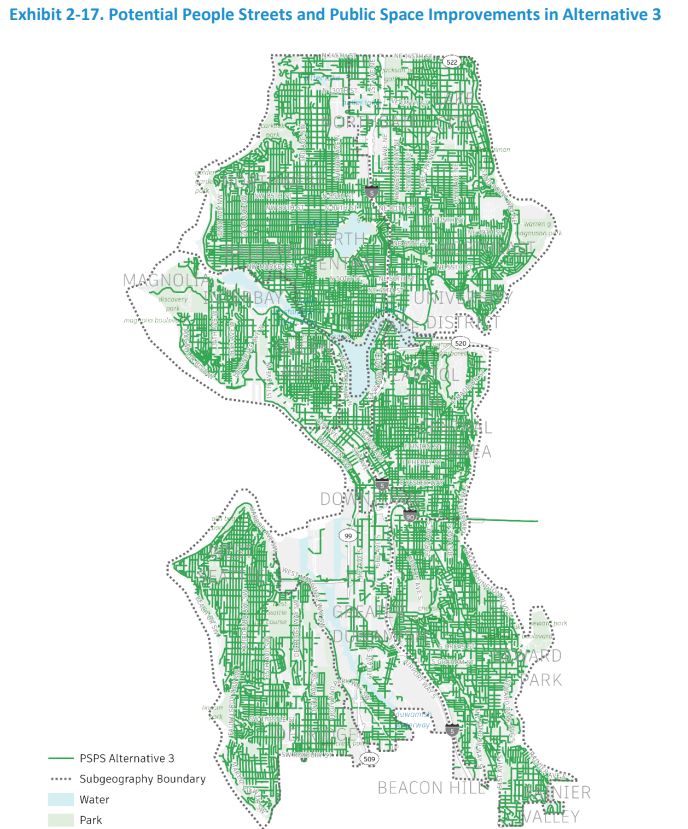

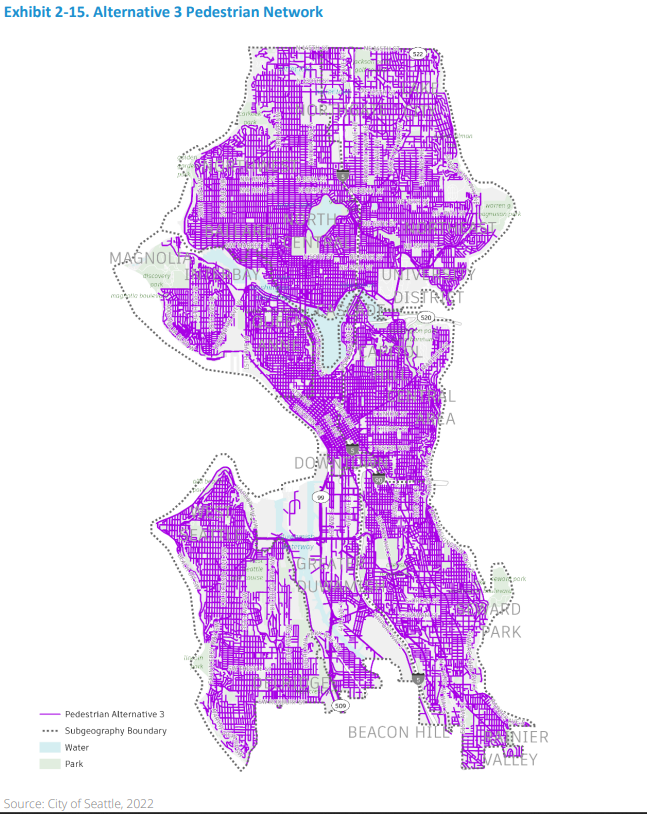

- Alternative 3 – Rapid Progress: “Alternative 3 focuses on the expansion of Seattle’s pedestrian, bicycle, and transit connections. The pedestrian network increases by 848 linear miles of sidewalks, the bicycle network adds 385 miles with facilities, an additional 76 miles of streets receive additional PSPS improvements, and an additional 123 miles are dedicated as transit corridors. In this alternative, the City fully implements overarching policies of the Seattle Transportation Plan with a greater expansion of PSPS, electrification infrastructure, a wider range of community and mobility hubs, and mobility management strategies in concert with the region. The existing freight network is expanded to include 19 miles of shared freight- and- bus (FAB) lanes.”

With Alternative 3, Seattle could reach almost as high as Paris has already achieved in car traffic reductions — or vehicle miles traveled (VMT) reductions in more jargon-y terms — dropping as much as 40% in an all-in full buildout scenario. “Alternative 3 could offer up to roughly 40% reductions in VMT attributable to additional mobility management strategies,” Chapter 3 of the Draft EIS notes.

However, because Seattle’s specific targeted outcomes were not integrated into the draft Seattle Transportation Plan (even with its 610-page technical report) and only released after the fact in the 444-page environmental statement and 82-page climate framework, it makes the earlier plan harder to decipher or offer meaningful feedback regarding how exactly we get there. The lack of specific action plans caused The Urbanist‘s contributing editor, Ryan Packer, to note the proof of concept would be in the City’s follow through rather than in its ambitious visioning exercises and pretty words. Meanwhile, needing to look across three massive documents to find all the City’s desired outcomes is hardly user-friendly.

A chart from the Draft EIS neatly summarizes the differences with Alternative 3 leagues ahead of the “no action” Alternative 1 on all fronts, and also considerably more expansive that the Alternative 2 “moderate pace” buildout.

No charts were offered to show how SDOT would achieve such a sharp uptick in project output on a practical basis — although soon-to-be-released plans to renew Seattle’s transportation levy could offer more guidance on that front.

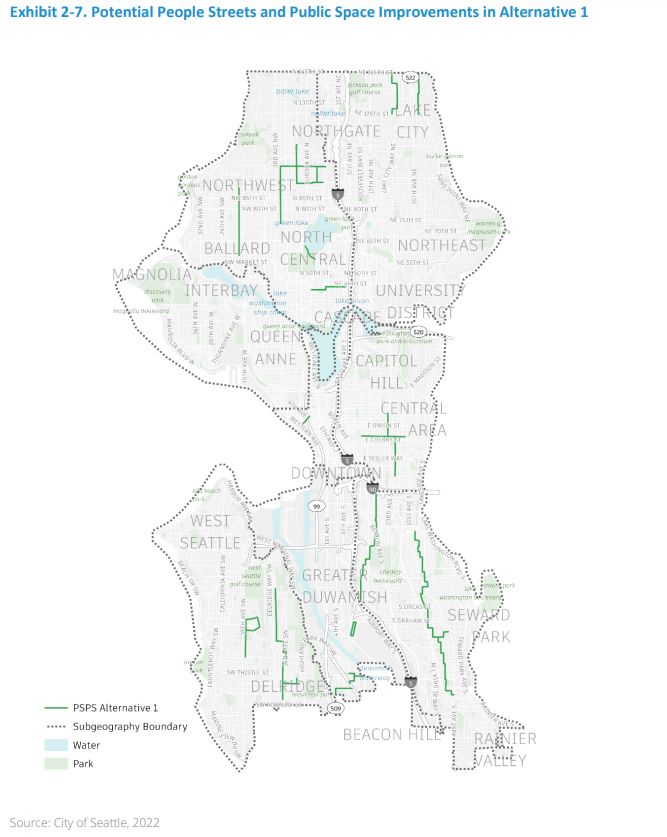

Another chart breaks down the additional 76 miles of people streets into further funding buckets, which build on the city’s existing 29 linear miles of “stay healthy streets (limited traffic),” which were established during the pandemic (mostly by upgrading existing neighborhood greenways by adding more traffic diversions and signs).

To these existing 29 miles, Alternative 3 would add:

- 46 linear miles of “destination streets.”

- 29 linear miles of “strolling streets.”

- 2 linear miles of “event streets.”

Adding 76 miles of people streets would be a big step for a City whose forays into pedestrianization have been pretty timid and incremental and have sometimes seemed to avoid installing car-limiting bollards at all costs, from the waterfront to Capitol Hill. Even Pike Place amidst a bustling market remains car-centric despite a groundswell of support for pedestrianization and a notable road rage collision that could have been avoided.

However, SDOT’s Alternative 3 is also less bold than an existing crowd-sourced plan that advocacy group, Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, released in 2020 with 130 miles of pedestrianized people streets to stitch a network across the city.

To further muddy the waters, the City’s definition of its new people streets categories is quite broad. Destination streets are “in the heart of a neighborhood with a high density of destinations — shops, restaurants, cultural centers, and more,” the agency wrote. “Improvements to these would make it safer and more enjoyable to walk and roll across and along these streets.” Thus, the degree to which these streets are car-free remains undefined.

SDOT’s definition of “strolling streets,” at least, notes that “vehicle volumes and speeds would be low.” The agency notes “strolling” improvements to these local streets could include any of the following:

- Lots of trees and climate-resilient landscaping;

- Abundant café seating and social activity;

- Streets for walking, rolling, and biking only (no vehicles);

- Plazas for gathering, playing, and connecting.

With these broad parameters, we could imagine some strolling streets could be car-free, but it’s not an inherent feature at this point. Likewise, the agency defines “event streets” as improvements to make it easier for streets to host events like farmer’s markets, but it’s anybody’s guess what that would entail.

If the City is envisioning reducing car traffic (or VMT) by 20% by 2030 to meet Seattle’s climate goals and by 40% to meet the most optimistic projections of Alternative 3, one would also hope it be brave enough to stridently define a people-first, car-free street as a concept it has in its toolbox. Then, one would hope the gumption to build it would follow.

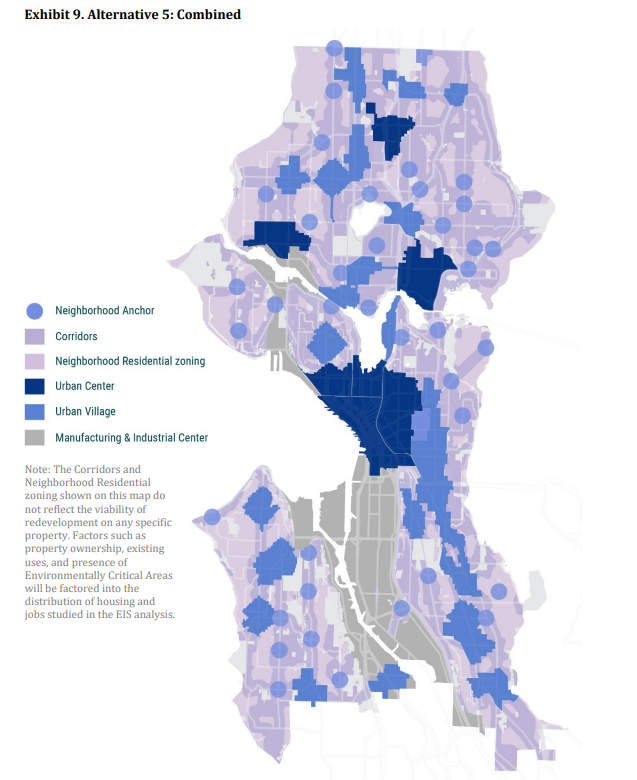

The Draft EIS notes that Alternative 3 is the most supportive of future growth and a denser land use pattern. Thus, it would pair well with Alternative 5, the most transformative land use plan the Harrell administration is considering — or arguably Alternative 6, which goes even farther but hasn’t made it into the Draft EIS despite being favored by housing advocates, including The Urbanist.

“Overall, Alternative 3 represents the most comprehensive and transformative approach to improving the City’s transportation network and is most supportive of broad changes to the land use pattern,” the City wrote. “Transit system improvements are also the most frequent, with the most dedicated transit corridors, light rail stations, and RapidRide corridors. This alternative introduces more EV charging infrastructure required in new development and additional EV infrastructure in public streets. These improvements create the most access to community assets in areas of the city beyond frequent transit corridors and outside of urban village/urban center boundaries.”

Electrifying car fleets and adding charging infrastructure get considerable emphasis across the plans. The climate framework envisions electric car trips jumping from 1% of trips to 10% by 2030.

However, safe streets advocates have often pointed out that reducing car speeds, reducing the size of vehicles, and limiting car traffic volumes (especially in pedestrian-heavy environments like cities) are effective at reducing road deaths and injury collisions and relatedly enticing more people to walk, roll, and bike their trips. Simply electrifying the same fleet without following through on VMT reductions and designing safer cars and streets may not be effective toward that goal. Because of their large batteries, electric cars are heavier than their internal-combustion counterparts and their superior acceleration makes them capable of delivering those heavier blows at greater speeds.

More than doubling the share of trips happening on bikes and scooters is going to take a commitment to designing safe streets. Otherwise, too many users will have close calls and serious collisions and give up.

More than doubling transit ridership, meanwhile, will take serious transit priority with an aggressive expansion of service and buildout of bus lanes — even where motorists or neighboring businesses raise a stink. With King County Metro still struggling to hire enough bus drivers and mechanics, Seattle can’t afford to be wasting the precious bus service hours it has on routes gridlocked in traffic — case in point the floundering Route 8. Beyond being a more efficient use of driver and bus resources, faster and more reliable bus service will be more enticing to riders and attract more ridership, as a recent Commute Seattle survey showed. A virtuous cycle is within reach if Seattle can commit to a transit priority.

While urbanists and climate hawks can quibble about the implementation details and bolder plans left on the cutting room floor, the combination of a Rapid Progress Alternative 3 for transportation with a Combined Alternative 5 for housing growth would be a gamechanger opening up a host of new possibilities. Implemented well, it could be truly transformational for a city with aspirations of leading on climate and on housing, even with a string of mayors who haven’t yet gotten to the follow through stage.

Like it or not, the follow through stage is upon us, and a greener Seattle that works better for everyone is the reward for seeing it through.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrianizing streets, blanketing the city in bus lanes, and unleashing a mass timber building spree to end the affordable housing shortage and avert our coming climate catastrophe. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in East Fremont and loves to explore the city on his bike.